Where Does Child Protective Services Budget Come From / Who Administers Funds

Summary. California's children and family programs include an array of services to protect children from abuse and fail and to keep families safely together when possible. This analysis: (1) provides plan background; (two) outlines the Governor's proposed 2022‑23 budget for children and family programs, including child welfare services (CWS) and foster care programs; (iii) provides implementation updates on a number of programs that were funded in 2021‑22; and (four) raises questions and issues for the Legislature to consider as it evaluates the budget proposal.

Programme Background

CWS. When children experience abuse or neglect, the state provides a diverseness of services to protect children and strengthen families. The state provides prevention services—such every bit substance employ disorder treatment and in‑home parenting support—to families at risk of child removal to help families remain together, if possible. When children cannot remain safely in their homes, the state provides temporary out‑of‑home placements through the foster care organization, often while providing services to parents with the aim of safely reunifying children with their families. If children are unable to render to their parents, the state provides assistance to plant a permanent placement for children, for example, through adoption or guardianship. California'south counties carry out children and family unit programme activities for the state, with funding from the federal and land governments, along with local funds.

Federal Funding. When a family becomes involved with the child welfare or foster care system, and that family meets federal eligibility standards based on income and other factors, states may claim federal funds for part of the cost of providing care and services for the child and family unit. State and local governments provide funding for the portion of costs not covered by federal funds, based on cost‑sharing proportions determined by the federal government. These federal funds are provided pursuant to Championship IV‑E (related to foster care) and Title 4‑B (related to child welfare) of the Social Security Act.

2011 Realignment. Until 2011‑12, the land Full general Fund and counties shared significant portions of the nonfederal costs of administering CWS. In 2011, the land enacted legislation known every bit 2011 realignment, which dedicated a portion of the land's sales and use taxation and vehicle license fee revenues to counties to administer child welfare and foster care programs (along with some public condom, behavioral wellness, and developed protective services programs). As a outcome of Suggestion 30 (2012), under 2011 realignment, counties either are not responsible or just partially responsible for CWS programmatic price increases resulting from federal, state, and judicial policy changes. Proposition 30 establishes that counties only need to implement new country policies that increase overall programme costs to the extent that the state provides the funding for those policies. Counties are responsible, even so, for all other increases in CWS costs—for case, those associated with rising caseloads. Conversely, if overall CWS costs fall, counties retain those savings.

Continuum of Care Reform (CCR). Beginning in 2012, the Legislature passed a series of legislation implementing CCR. This legislative package makes cardinal changes to the fashion the state cares for youth in the foster intendance system. Namely, CCR aims to: (ane) cease long‑term congregate care placements; (2) increment reliance on home‑based family placements; (3) better admission to supportive services regardless of the kind of foster care placement a child is in; and (4) employ universal kid and family unit assessments to ameliorate placement, service, and payment rate decisions. Under 2011 realignment, the state pays for the net costs of CCR, which include up‑front implementation costs. While not a principal goal, the Legislature enacted CCR with the expectation that reforms eventually would lead to overall savings to the foster care system, resulting in CCR ultimately becoming cost neutral to the country. (We note that CCR is a multiyear effort—with implementation of the various components of the reform bundle beginning at dissimilar times over several years—and the country continues to work toward full implementation in the current year.)

Extended Foster Intendance (EFC). At around the same time as 2011 realignment, the state as well implemented the California Fostering Connections to Success Act (Chapter 559 of 2010 [AB 12, Beall]), which extended foster intendance services and supports to youth from age eighteen up to age 21, offset in 2012. To exist eligible, a youth must have a foster care order in effect on their 18th altogether, must opt in to receive EFC benefits, and must meet sure criteria (such as pursuing higher education or piece of work grooming) while in EFC. Youth participating in EFC are known as non‑minor dependents (NMDs). In addition to case management services, NMDs receive support for independent or transitional housing.

Foster Placement Types. As described above, when children cannot remain safely in their homes, they may be removed and placed into foster care. Counties rely on various placement types for foster youth. Pursuant to CCR, a Child and Family Squad (CFT) provides input to assistance determine the virtually appropriate placement for each youth, based on the youth'due south socio‑emotional and behavioral health needs, and other criteria. Placement types include:

- Placements With Resources Families. For almost foster youth, the preferred placement type is in a home with a resource family unit. A resource family may exist kin (either a non‑custodial parent or relative), a foster family approved by the county, or a foster family approved by a private foster family agency (FFA). FFA‑approved foster families receive additional supports through the FFA and therefore may intendance for youth with college‑level physical, mental, or behavioral health needs.

- Congregate Care Placements. Foster youth with intensive behavioral health needs preventing them from beingness placed safely or stably with a resource family unit may be placed in a Curt‑Term Residential Therapeutic Program (STRTP). These facilities provide specialty behavioral health services and 24‑hour supervision. STRTP placements are designed to be curt term, with the goal of providing the needed care and services to transition youth safely to resource families. Pursuant to new federal requirements—specifically the Family First Prevention Services Human activity (FFPSA), described more than below—STRTPs must meet new federal criteria to continue receiving Title IV‑E funding for federally eligible youth. In improver, STRTP placements must be approved by a "Qualified Individual" (QI) such as a mental health professional.

- Independent and Transitional Placements for Older Youth. Older, relatively more self‑sufficient youth and NMDs may be placed in supervised independent living placements (SILPs) or transitional housing placements. SILPs are independent settings, such as apartments or shared residences, where NMDs may alive independently and continue to receive monthly foster care payments. Transitional housing placements provide foster youth ages 16 to 21 supervised housing likewise as supportive services, such as counseling and employment services, that are designed to assist foster youth achieve independence.

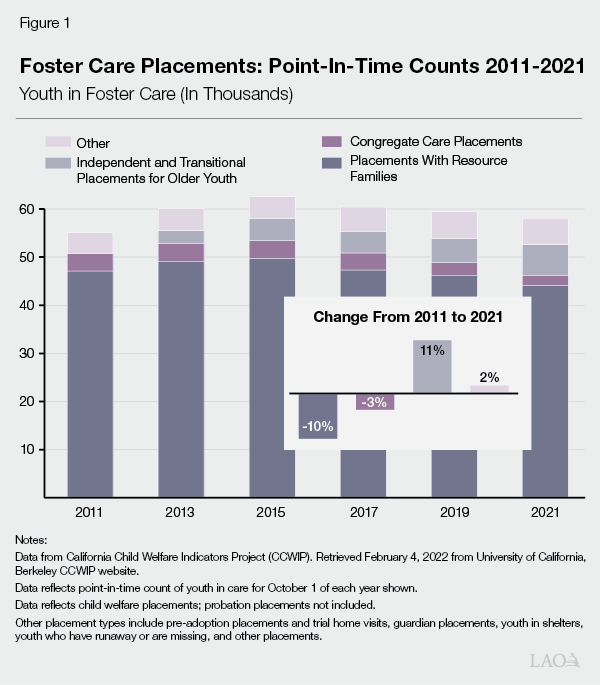

Total Foster Care Placements Have Remained Stable, With Shifts in Placement Types. Over the by decade, the number of youth in foster care has remained around 60,000 (ranging from around 55,000 to around 63,000 at whatsoever bespeak in fourth dimension). While the total number of placements has remained stable, the predominance of various placement types has shifted over fourth dimension. In particular, in line with the goals of CCR, besiege care placements take decreased, while more than contained placements have increased since the implementation of EFC. Effigy 1 illustrates changes in foster placements over time.

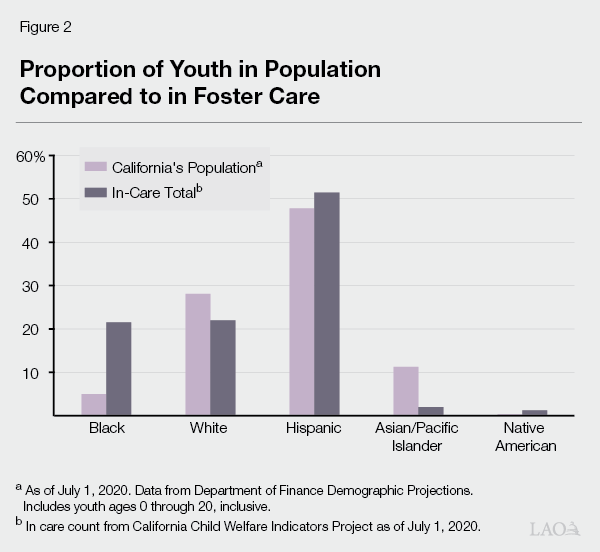

Foster Youth Are Disproportionately Low Income, Black, and Native American. A broad body of enquiry has found that families involved with child protective services are disproportionately poor and overrepresented by certain racial groups, and are frequently single‑parent households living in low‑income neighborhoods. In California, Black and Native American youth in particular are overrepresented in the foster care arrangement relative to their respective shares of the state's youth population. As illustrated in Figure 2, the proportions of Black and Native American youth in foster care are around iv times larger than the proportions of Blackness and Native American youth in California overall. While the information displayed in Effigy ii is point in fourth dimension, these disproportionalities have persisted for many years. We note that the figure displays aggregated state‑level data; disproportionalities differ across counties.

FFPSA. Historically, one of the chief federal funding streams available for foster care—Title 4‑East—has not been available for states to use on services that may foreclose foster intendance placement in the showtime place. Instead, the use of Championship 4‑E funds has been restricted to support youth and families only after a youth has been placed in foster care. Passed as office of the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Human action, FFPSA expands allowable uses of federal Title Iv‑E funds to include services to help parents and families from inbound (or re‑entering) the foster care system. Specifically, FFPSA allows states to claim Title Four‑E funds for mental health and substance abuse prevention and treatment services, in‑home parent skill‑based programs, and kinship navigator services once states run across certain conditions. FFPSA additionally makes other changes to policy and practise to ensure the appropriateness of all congregate care placements, reduce long‑term congregate intendance stays, and facilitate stable transitions to home‑based placements.

The police is divided into several parts; Role I (which is optional and related to prevention services) and Part IV (which is required and related to congregate care placements) have the most meaning impacts for California. States were required to implement Function IV by Oct one, 2021 in order to foreclose the loss of federal funds for besiege care. States may non implement Part I until they come into compliance with Part IV.

Overview of Governor'south Budget

Proposed Spending in 2022‑23 Decreases Significantly Compared to 2021‑22, Primarily Due to Expiration of One‑Fourth dimension and Limited‑Term Funding. Equally shown in Figure 3, total funding for child welfare is proposed to decrease past more than than $ane billion (more than $700 million General Fund) between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. This decrease was expected as a number of ane‑time/express‑term program augmentations were included in the 2021‑22 budget and are not proposed to continue in 2022‑23. Notably, the state'southward pandemic support inside child welfare also largely expires in 2021‑22, and several significant one‑fourth dimension/limited‑term federal augmentations are projected to end in the current twelvemonth likewise. Beyond these specific changes, the lower proposed country and federal funding amounts in 2022‑23 besides reverberate some lower projected spending on home‑based family care rates. The principal drivers of the year‑over‑yr subtract are detailed inFigure 4.

Effigy three

Changes in Local Assist Funding for Child Welfare and Foster Intendance

Includes Child Welfare Services, Foster Intendance, AAP, KinGAP, and ARC (In Millions)

| Full | Federal | State | County | Reimbursements | |

| 2021‑22 revised budget | $9,872 | $3,622 | $1,494 | $4,564 | $192 |

| 2022‑23 Governor'due south Upkeep | 8,756 | three,056 | 761 | 4,723 | 215 |

| Alter From 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | ‑$1,116 | ‑$566 | ‑$732 | $159 | $23 |

| AAP = Adoption Help Program; KinGAP = Kinship Guardianship Assistance Payment; and ARC = Canonical Relative Caregiver | |||||

| Note: Does non include Kid Welfare Services automation. | |||||

Effigy 4

Primary Drivers of Overall Child Welfare Spending Decreases

(In Millions)

| Item | Full Funds Change From 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | General Fund Modify From 2021‑22 to 2022‑23 | Reason |

| FFPSA Part I | ‑$286 | ‑$222 | One‑time funding in 2021‑22 to help counties begin implementing Championship IV‑East prevention services. |

| Family Starting time Transition Act—Funding Certainty Grant | ‑250 | — | Express‑term federal grants to support counties transitioning after the stop of Championship Iv‑Due east Waiver Demonstration Projects. |

| Addressing Complex Care Needs | ‑122 | ‑121 | Some ane‑time support for foster youth requiring complex care, including intensive behavioral health needs. Nosotros note that around $20 meg total funds ($18 million GF) is ongoing. |

| COVID‑19 temporary FMAP increase | ‑100 | — | Federal augmentation projected to terminate June thirty, 2022. |

| Ane‑time funding to counties | ‑85 | ‑85 | One‑time support in 2021‑22. |

| COVID‑19 pandemic assistance for resource families | ‑eighty | ‑lxxx | One‑time funding in 2021‑22 to provide lump‑sum payments to resources families in response to pandemic. |

| COVID‑19 support for former NMDs and flexibilities inside EFC | ‑55 | ‑49 | Limited‑term funding to support NMDs and former NMDs who would accept aged out or lost eligibility for EFC. Back up ended December 31, 2021. |

| COVID‑19 back up for STRTPs | ‑42 | ‑42 | Ane‑time funding in 2021‑22 for STRTPs experiencing negative financial impacts due to the pandemic. |

| FFPSA Part IV | ‑30 | ‑iii | Some one‑time support to begin implementing new congregate care requirements. We note that around $57 1000000 total funds ($29 million GF) is ongoing. |

| Placement prior to approving | ‑18 | ‑11 | Maximum elapsing decreases from 120 days (with possible extension upward to 365 days) to xc days. |

| Transition from 16+ bed STRTPs | ‑10 | ‑10 | One‑time funding in 2021‑22 to support STRTPs determined to be IMDs and therefore no longer eligible for Medicaid federal fiscal participation. |

| COVID‑19 support for Family unit Resource Centers | ‑half dozen | ‑6 | Express‑term funding for Family Resource Centers in response to pandemic. Expenditure authority ends June 30, 2022. |

| COVID‑19 rate flexibilities for resource families | ‑5 | ‑3 | Limited‑term selection to increase foster care monthly maintenance payment rates for families directly impacted past COVID‑19. Back up ended December 31, 2021. |

| COVID‑nineteen support for state administered contracts | ‑two | ‑2 | Limited‑term funding for parent and youth helpline and laptop and prison cell phone distribution in response to pandemic. Expenditure authorisation ends June 30, 2022. |

| Other Net Changes | ‑25 | 97 | Includes increases and decreases, including new proposed funding and monthly assistance payment rate and caseload changes. |

| Totals | ‑$1,116 | ‑$732 | |

| FFPSA = Family unit Kickoff Prevention Services Human activity; GF = General Fund; FMAP = federal medical help percentage; NMDs = non‑minor dependents; EFC = extended foster intendance; STRTP = Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Programs; and IMDs = Institutions for Mental Affliction. | |||

Majority of Pandemic Response Would End in the Current Year. Since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, California has provided a variety of fiscal supports and flexibilities to families involved with the kid welfare and foster care systems. In addition to the supports described in Figure 4, the state besides provided cash cards to families at risk of child removal (including eligible families on counties' Emergency Response and Family Maintenance caseloads) using 2019‑20 and 2020‑21 funding. A few components of the state's pandemic response within child welfare are proposed to proceed in 2022‑23. Specifically, the administration proposes to provide: (i) $fifty million 1 time for counties to increment their emergency response chapters ($l meg one time for this purpose likewise was included in the 2021‑22 budget), and (two) $4.7 meg one fourth dimension to continue supporting the operation of the parent and youth helpline. (We talk over the Department of Social Services' [DSS's] progress disbursing pandemic response funds provided in the current year in more than particular below.)

Governor'due south Proposals Include Express New Not‑Pandemic Spending. While overall child welfare spending is proposed to decrease significantly from 2021‑22 to 2022‑23, the Governor's budget does include a few new spending proposals. These proposals, described below, would result in new one‑time spending of around $five.4 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and around $1 million General Fund ongoing.

- Addressing Resource Family Approval (RFA) Backlog: $four.four million i time to back up counties in addressing the current backlog of resource family unit applications with approval times over 90 days. Funding would provide overtime pay to existing staff to accost the backlog.

- Foster Youth to Independence (FYI) Pilot Program: $1 million one time to support counties piloting the federal Housing and Urban Development FYI voucher program. The state launched the airplane pilot in the second one-half of 2021 using federal Chafee funding, which expires in September 2022. The Governor's budget proposal would provide state resource to continue the pilot for an additional two years.

- Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Appeals: $227,000 ongoing for social worker costs related to preparing and filing appeals for denied federal SSI applications for foster youth approaching 18 years of age. Electric current law requires counties to screen sixteen‑17 yr olds for potential SSI benefits and file initial claims; the proposed funding would back up appeals when those initial claims are denied.

- Family Finding Support and Engagement: $750,000 ongoing to provide technical assistance and training for county welfare agencies in back up of family unit finding and engagement activities for foster youth.

Other Programs Benefitting Foster Youth Proposed Nether Different Departments. The Governor's budget includes two pregnant proposals benefitting foster youth and former foster youth outside the health and human being services agency.

- Higher Education Supports: $10 million ongoing to aggrandize NextUp at California Customs Colleges, and $18 one thousand thousand ongoing to support similar programs at the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems. NextUp'southward current funding is $twenty million ongoing, and the program currently is provided at 20 community college districts. The programme provides a broad range of services to current and former foster youth, including outreach and recruitment, academic counseling, tutoring, book and supply grants, and referrals to health and mental health services. The proposed $10 million augmentation would expand the program to an additional x customs college districts. The proposed $xviii 1000000 for CSU and UC would provide similar support for foster youth programs across CSU and UC campuses. We talk over these proposals more than in our assay of higher education programs hither.

- Taxation Credit for Former Foster Youth: $20 1000000 estimated reduction in revenue to provide fully refundable revenue enhancement credits of around $one,000 to former foster youth historic period 18 through 25 who are eligible for the California Earned Income Tax Credit. The administration estimates around 20,000 youth would claim the credits each year, out of more than 70,000 potentially eligible youth.

Implementation Updates

In this section, we describe the progress that DSS has made in implementing various programs funded in the current year.

Pandemic Response. The state has been providing diverse supplemental supports for child welfare involved families since the onset of the pandemic. As described above, many of these supports expired Dec 31, 2021. For supports newly funded in 2021‑22, some funds have not yet been disbursed to beneficiaries as DSS has needed fourth dimension to institute guidelines and decide specific allocations. Figure 5 summarizes the pandemic supports funded inside child welfare, along with the funding amounts, status, and other information.

Figure 5

Summary of Country Funds for Pandemic Response Within Child Welfare

General Fund (In Millions)

| Assistance Area | 2019‑twentya | 2020‑21b | 2021‑22c | 2022‑23d | Implementation Status |

| Greenbacks cards for families at risk of foster care | $27.8 | $28.0 | — | — | Payments of up to $1200 per eligible family are being disbursed in several rounds, with the latest round launched in January 2022. Payments will continue until funds are fully expended. Greenbacks cards are issued to caregivers by a third‑political party vendor. Equally of January 31, 2022, payments had been issued for more than than 38,000 children. |

| Family unit Resource Centers funding | 3.5 | 7.0 | $6.0 | — | Funding has been issued to 378 FRCs in 53 counties, and is expected to serve more 250,000 individuals. FRCs are using funding to cover costs for services such as parenting resources, counseling, education and altitude learning, as well as for cloth goods and for staffing. |

| Land contracts for engineering distribution (laptops, cell phones) and helpline for youth and familiese | — | two.0 | ane.8 | $4.7 | Contracts have been issued to iFoster to distribute laptops and cell phones primarily for remote learning, and to Parents Anonymous to operate the California Parent and Youth Helpline. Through Dec 2021, iFoster distributed 570 laptops and 162 cell phones, and the Helpline had fielded more than 27,000 calls, texts, and live chats. The 2022‑23 Governor's Budget proposal includes ane‑time funding in the budget year with three years of spending potency to go along supporting the Helpline. |

| Administrative workload for child welfare social workers (overtime, pandemic outreach) | v.0 | — | — | — | Funding provided during the early months of the pandemic. |

| Rate flexibilities for resources families directly impacted by pandemicf | three.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | — | DSS did not track how many families received charge per unit flexibilities (rather, the section receives aggregated claims information from counties). We note that, since these flexibilities expired at the finish of the 2021 agenda year, families impacted by the Omicron variant in early 2022 are not eligible. |

| Flexibilities and expansions for NMDs/former NMDs who plow 21 or otherwise lose eligibility for EFC due to pandemic | 1.8 | 37.4 | 49.i | — | Federal flexibilities and expansion ended September xxx, 2021. State flexibilities and expansion ended December 31, 2021. DSS estimates that about 5000 youth benefitted from this expanded back up. |

| Pre‑approval funding for emergency caregivers, beyond 365 days | 1.3 | 1.2 | — | — | DSS did non runway how many families received rate flexibilities (rather, the department receives aggregated claims data from counties). |

| Grants to STRTPs that experienced increased expenses and revenue losses due to pandemic | — | — | 42.0 | — | Equally of January 31, 2022, funding had not yet been issued to STRTPs. According to an initial assessment of STRTPs' total pandemic losses, facilities are requesting around $115 million—most three times more than total funding available. |

| Pandemic assist payments for resource families, emergency caregivers, tribally approved homes, and guardians | — | — | lxxx.0 | — | Equally of Jan 31, 2022, funding had non yet been issued to caregivers. DSS estimates payments will brainstorm going to caregivers in February 2022, and that the average help amount will exist about $1200‑$1500. The maximum assist payment will exist $5000 per caregiver. |

| Increase emergency response kid welfare social workers | — | — | fifty.0 | 50.0 | DSS has indicated counties must opt in (by March four, 2022) to receive 2021‑22 funding. Funds provided in 2021‑22 and funds proposed for 2022‑23 are available over 4 years. |

| Totals | $42.5 | $79.ii | $232.3 | $54.7 | |

| aFor 2019‑xx, funds were provided Apr through June 2020. Activities were approved past the Legislature through the Section 36.00 letter process. bFor 2020‑21, pandemic‑response activities were proposed for January through June 2021 every bit part of the 2020‑21 Governor'due south Budget Proposal for all actions other than flexibilities and expansions for NMDs. (Flexibilities and expansions for NMDs were included in the 2020‑21 Budget Deed.) For all other activities for 2020‑21, the Legislature canonical the listed amounts as part of the Budget Nib Jr. package in April 2021. c 2021‑22 funding expired Dec 31, 2021 for applied science distribution, rate flexibilities for resource families, and flexibilities and expansion for NMDs/former NMDs. 2021‑22 funding is predictable to stop June 30, 2022 for Family Resource Centers, grants to STRTPs, and pandemic assistance payments to caregivers. 2021‑22 funding volition keep until funds are fully expended for cash cards for families at take chances of foster care. d Funding is proposed for July 1, 2022‑June 30, 2023 with multiple years of expenditure authorization for the helpline and increase in emergency response child welfare social workers. eFunding for land contracts for technology and hotlines in 2019‑twenty was included in the amount for Family Resource Centers funding. fIn add-on to the General Fund corporeality, $five.678 million funding from DREOA is budgeted for foster intendance rate flexibilities in 2020‑21. | |||||

| Notes: Where applicative, amounts include help plus administrative costs. 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 amounts reverberate 2021 May Revision estimates. | |||||

| NMDs = non‑minor dependents; EFC = extended foster care; STRTPs = Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Programs; and DREOA = Disaster Response Emergency Operations Account. | |||||

FFPSA Congregate Intendance Requirements (Part IV). As described in the background section of this mail service, states were required to come into compliance with Role IV of FFPSA by October i, 2021. The 2021‑22 budget included around $32 million Full general Fund for the state's share of new costs required to meet the requirements of FFPSA Office Four. (Refer to our 2021‑22 spending plan analysis of child welfare programs here for a more detailed clarification of these requirements.) Kickoff in late September 2021, DSS issued guidance to counties regarding the various new requirements of the law, including assessments of congregate care placements by QIs, nursing services, aftercare services, court review and case plan requirements, and tracking requirements for otherwise federally eligible youth whose foster placement does non meet criteria for federal fiscal participation. The department has been facilitating technical assist since October to back up counties in meeting these new requirements and has reported that overall counties take been able to meet federal deadlines—overcoming some initial challenges particularly related to QI assessments.

FFPSA Optional Title IV‑Eastward Prevention Services (Part I). Regarding optional Title Four‑Due east prevention services which California intends to implement as allowed by Part I of FFPSA, the 2021‑22 budget included one‑time General Fund resources of around $222 1000000 for this purpose. (Again, refer to our 2021‑22 spending programme analysis of kid welfare programs hither for a more than detailed description.) This funding has non nonetheless been allocated or disbursed, every bit the section continues to work on its federally required Title IV‑E Prevention Services State Program and to develop the block grant allotment methodology and guidance for counties and tribes interested in opting in. In add-on, in lodge to begin claiming Title 4‑East funds for prevention services, the land must be able to come across federal requirements around tracking per‑child prevention spending. Such tracking is beyond California's child welfare data system's current capacity. The department and stakeholders are working to determine what automation solution(s) will be feasible. Stakeholders have expressed concern that the solution could accept significant time—potentially several years—to develop. Whether an interim solution is feasible, how rapidly that solution could exist developed, and what that would entail is unclear.

Addressing Complex Care Needs. The 2021‑22 upkeep package included implementing legislation to reduce California's reliance on out‑of‑land placements—ultimately prohibiting any new out‑of‑land congregate care placements showtime July 1, 2022 (with limited exceptions). To facilitate this statutory change, the 2021‑22 budget provided around $139 million General Fund (including $18 million ongoing) to develop and strengthen the systems and supports necessary to serve youth with complex care needs in state. Specifically, allocations include: (1) child‑specific funding bachelor through an individual asking ($18 one thousand thousand ongoing), (two) funds to back up county capacity building ($43 meg one time), and (3) funds to support a five‑yr Children's Crunch Continuum Pilot ($60 million one time). (Refer to our 2021‑22 spending programme analysis of kid welfare programs here for a more detailed clarification of what these components entail.) In Oct through December 2021, DSS issued guidance and allocations for counties to merits funds for the first and second funding components described above. A Asking for Proposals (RFP) process will be required for the third funding component—the Children's Crisis Continuum Pilot. DSS anticipates releasing RFP guidance in the coming weeks.

Bringing Families Domicile (BFH) Augmentation. The BFH Program provides financial assistance and housing‑related wraparound supportive services to reduce the number of families in the kid welfare system experiencing or at risk of homelessness, to increase family unit reunification, and to foreclose foster care placement. BFH received two General Fund funding tranches—each expendable over 3 years—in fiscal years 2016‑17 ($10 million) and in 2019‑20 ($25 1000000). Twelve counties received funding in the starting time grant bike, and the 2019‑20 funds were awarded to 22 counties and one tribe. The program requires a dollar‑for‑dollar match. As of August 2021, more than than 1,600 families had been permanently housed through BFH, with the boilerplate assistance per instance around $40,000 and average assist time around one twelvemonth and seven months (with significant variation beyond counties).

The 2021‑22 upkeep bundle included $92.five million General Fund one time (expendable over three years) to broaden the program. Counties and tribes are not required to provide matching funds to receive these funds. The Governor's 2022‑23 budget proposal includes an additional $92.5 1000000 augmentation equally agreed to as part of the 2021‑22 package. DSS issued guidance to counties nearly the availability of the 2021‑22 not‑competitive allocations for all 58 counties (and a tribal set up aside) in mid‑February; county welfare departments will indicate whether they accept their allocations by the end of March. DSS indicated that developing the necessary guidance and allocation methodology required extra time given the significant size of the augmentation.

Ongoing CCR Implementation. The state is continuing to work toward full implementation of CCR in the current year. Effigy 6 displays the net costs of CCR budgeted in 2022‑23, relative to those in 2021‑22.

Specific elements of CCR implementation ongoing in the current year include:

- CFT Meetings. CFT meetings involve the youth, family members, and various professionals (for example, social workers, mental health professionals, and QIs) and community partners (for case, teachers) for the purpose of informing case plan and placement goals and strategies to attain them. Since 2017, guidance from DSS has indicated that all foster youth and NMDs should receive CFT meetings within threescore days of entering intendance and periodically thereafter. However, progress remains to attain full implementation. As of September 2021, around 80 pct of youth had received a CFT meeting and around 80 percent of those meetings happened on time. These statistics have not changed significantly from 1 yr prior.

- Child and Boyish Needs and Strengths (CANS) Assessments. In 2018, DSS selected the CANS assessment tool as the functional tool to be used in CFT meetings. CFTs began implementing the tool in 2019—with kid welfare and behavioral health staff jointly responsible for completing all required CANS information. (The CANS tool also is used past the QI to come across FFPSA congregate intendance cess requirements, every bit of October ane, 2021.) Guidance from DSS required child welfare agencies to begin entering CANS data into an automatic organization by July 1, 2021. However, not all counties currently have access to this system. Moreover, staff must undergo training and a process to gain access to the system to be able to use it. In addition, there are some CANS reporting differences beyond the child welfare and behavioral health systems that DSS and the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) are working to address, while current coordination between child welfare and behavioral health staff to complete all CANS requirements differs by canton. Given these challenges, DSS cannot even so provide full data almost CANS usage.

- Level of Care (LOC) Protocol Tool. Beginning Apr 1, 2021, all dwelling house‑based family care placements with resource families were eligible to receive LOC rates ii through four and Intensive Services Foster Care, based on assessed demand using the LOC Protocol Tool. Equally of October 2021, more than x,000 placements had received an LOC assessment, and from April to October 2021, the proportion of placements receiving a rate other than the bones rate increased slightly (although more than sixty percent of new placements continued to receive the bones rate). LOCs previously had been rolled out commencement in 2018 for new entries placed with FFAs. Stakeholders have raised various concerns with the LOC Protocol Tool since its implementation and take suggested that the CANS assessment could be used for rate determinations in lieu of a split tool. DSS continues to explore the potential usage of CANS for this purpose.

- RFA and Placement Prior to Approval (PPA). To become eligible to provide care to foster youth and receive foster intendance maintenance payments, households must complete the RFA procedure. This process is universal for all foster caregivers, whether they are relatives or not‑relative foster families, although relatives may begin providing care to foster youth on an emergency basis prior to formal approval equally a resource family. Statute specifies that the maximum duration of PPA will decrease from 120 days (with possible extension upwards to 365 days) in 2021‑22 to 90 days (no extension possible) in 2022‑23. Every bit of the third quarter of 2021, median approving time was 120 days overall, and 109 days for PPA. These are similar fourth dimension lines relative to late 2019. RFA medians increased steadily throughout 2020 as a effect of the pandemic, reaching a peak of 150 days (140 days for PPA), but decreased again in 2021.

- STRTP Transition and Mental Wellness Program Approval. Group homes were required to meet STRTP licensing standards by December 31, 2020. One time licensed, STRTPs have 12 months to obtain mental health plan approval from DHCS. As of November 2021, in that location were 419 licensed STRTPs with a total capacity of 4,102. However, only 286 of those facilities had received mental health programme approval. Our current understanding is that near of the remaining facilities have submitted their mental wellness program applications and are going through the blessing process. We notation that STRTPs currently also are working to see new besiege care requirements nether FFPSA.

Effigy half dozen

CCR Costs: Governor's Upkeep for 2022‑23 Compared to 2021‑22 Revised Upkeep

(In Thousands)

| 2022‑23 | 2021‑22 | Change | ||||||

| Total | Nonfederal | Total | Nonfederal | Total | Nonfederal | |||

| HBFC Rate | $224,234 | $146,035 | $303,763 | $187,651 | ‑$79,529 | ‑$41,616 | ||

| PPA (statutory change July 1, 2022) | eleven,583 | 11,301 | 29,794 | 22,561 | ‑18,211 | ‑11,260 | ||

| CANS (child welfare workload just) | four,195 | 3,062 | 4,699 | 3,430 | ‑504 | ‑368 | ||

| CCR reconciliation for 2018‑nineteen | — | — | 7,089 | vii,089 | ‑seven,089 | ‑7,089 | ||

| CCR—contracts | 9,192 | 6,523 | eight,281 | 6,014 | 911 | 509 | ||

| Second level administrative review | 161 | 117 | 161 | 117 | — | — | ||

| CFTs | 90,502 | 66,066 | 80,148 | 58,593 | x,354 | 7,473 | ||

| RFA (funding for probation departments) | 5,795 | iv,230 | 5,795 | four,202 | — | 28 | ||

| RFA backlog (overtime funding for canton social workers) | 6,071 | 4,432 | — | — | 6,071 | 4,432 | ||

| LOC Protocol Tool | 9,988 | 7,291 | ix,973 | 7,291 | fifteen | — | ||

| SAWS | 500 | 209 | 500 | 209 | — | — | ||

| Totals | $362,221 | $249,266 | $450,203 | $297,157 | ‑$87,982 | ‑$47,891 | ||

| HBFC = home‑based family care; PPA = Placement Prior to Approving; CANS = Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths; CCR = Continuum of Intendance Reform; CFT = Child and Family Team; RFA = Resource Family unit Approval; LOC = level of care; and SAWS = Statewide Automatic Welfare System. | ||||||||

One‑Time Funding to Counties. The state provided $85 meg Full general Fund i‑time funding to counties for child welfare activities in 2021‑22. (The state provided a like ane‑time funding amount for this purpose in 2020‑21.) DSS released guidance specifying counties' individual allocations in Oct 2021.

LAO Comments

In this section, we provide comments and questions for the Legislature to consider. In the midst of the pandemic, DSS has been implementing major reforms and new programs, including new federal requirements around congregate care placements, efforts to build in‑state capacity to care for youth with complex needs, and ongoing CCR implementation. Both responding to the public health emergency, as well as carrying out major programmatic changes, has involved significant efforts at the state and local levels. While our comments focus on areas where improvement could be made or more information is needed, nosotros do not disbelieve the efforts DSS is making across its many programs.

Allocation of New Funds Provided in 2021‑22 Has Been Slow. As described to a higher place, some pregnant augmentations to kid welfare programs funded in the 2021‑22 budget have not been allocated or have been simply partially allocated more than than six months into the electric current fiscal year, including some pandemic back up for at‑risk families and foster caregivers, funding for the Children'southward Crunch Continuum Airplane pilot, and block grants for prevention services. Given these funding areas were legislative priorities during the 2021‑22 budget process, the Legislature may wish to ask the department what is needed to classify these 2021‑22 funds and how to improve upon future processes. Specific questions could include, for example:

- Does the department need additional back up or legislative direction in the current or budget year?

- Are at that place any lessons learned in 2021‑22 that the Legislature should incorporate into future legislation to ensure programs are implemented in a timely mode?

- Should statutory fourth dimension lines for programs—for example, Bringing Families Dwelling or the Children'south Crisis Continuum Airplane pilot—be extended, given delayed starts?

Progress Implementing Some Elements of CCR Seems to Accept Stalled. While all major elements of CCR implementation began prior to the current twelvemonth, some elements—such every bit universal usage of CFTs, CANS, and LOC Protocol—remain less‑than‑fully implemented. Other elements have yet to achieve their goals. For example, the RFA median approval time has not all the same reached the target of 90 days or less. Every bit total implementation of all components is critical to achieving the goals of CCR, the Legislature may wish to inquire the department what challenges are preventing full implementation, and what additional supports or guidance may be needed regarding those elements that have yet to be fully rolled out. For example:

- What assistance is needed for those counties that have faced challenges fully implementing CFTs and CANS assessments? For counties that have not been able to fully implement, how are QIs assessing congregate care placements (as required by FFPSA Part IV)?

- Have LOC assessments done to appointment focused on new placements or existing placements? How could utilization of the tool exist increased? Has the department addressed concerns from advocates regarding the LOC protocol tool? What is the status of exploring usage of the CANS tool for LOC assessments?

- What challenges are impacting STRTP mental health program approvals? Do STRTPs need additional support or technical assistance to secure those approvals?

Consider Whether Ending Pandemic Support in the Current Year Makes Sense. As COVID‑nineteen likely will remain a public health and economic challenge in the upkeep year and beyond, we recommend the Legislature closely consider the extent to which the Governor'south proposals properly prepare the land for this reality. Within child welfare, we suggest the Legislature consider what pandemic response activities may warrant continuation in the budget twelvemonth and also how to prioritize whatever connected supports. More than specifically:

- Are there specific supports provided in the current year—such every bit direct payments to at‑risk families or rate flexibilities for resource families straight impacted by COVID‑19—that the Legislature wishes to continue in the budget year, given the ongoing impacts of the pandemic, specially on vulnerable families?

- The Governor proposes to continue funding the California Parent and Youth Helpline in the upkeep yr. Does the Legislature agree this is a priority for ongoing pandemic support versus other activities?

Consider What Additional Guidance and Resource May Be Needed for FFPSA. Equally the country is in the early months of implementing FFPSA, we suggest the Legislature consider ways to ensure DSS continues to work with counties and stakeholders to determine where challenges remain and what additional guidance or back up is needed to meet new federal requirements around congregate intendance placements. Regarding the new federal option around prevention services, nosotros note there is item concern from stakeholders over how to track per‑kid prevention spending (as is federally required to exist able to claim Title Iv‑E funds for prevention services). Additionally, stakeholders continue to express concern that prevention services included in the state's Championship 4‑Due east Prevention Services Plan—which determines which services will exist eligible for federal financial participation in California—are limited. Part of this limitation stems from federal rules, but function of the limitation is from the way the state has decided to implement FFPSA. The Legislature may wish to consider providing more specific guidance to the department effectually broadening prevention services, besides equally whether providing temporary or ongoing funding to counties and Championship IV‑Eastward tribes would ensure children and families in all areas of the country could benefit from both Title IV‑Eastward and other prevention services. Specific issues the Legislature may wish to ask DSS to provide more than information well-nigh include:

- What steps is the department taking to understand any challenges or obstacles that counties and other stakeholders are encountering while implementing new congregate care requirements? For case, what technical assistance is DSS providing, and is DSS facilitating any workgroups or other processes involving stakeholders? Are there opportunities for the Legislature to be more involved in these processes to help ensure effective legislative oversight?

- When does DSS anticipate the state'due south Championship 4‑E prevention services plan will be canonical by the federal government?

- When does DSS anticipate guidance volition exist provided effectually implementing Title IV‑E prevention services?

- How does DSS wait child welfare agencies will meet the federal requirement of individual‑level expenditure tracking for prevention services? When does DSS conceptualize agencies will exist able to begin claiming Title IV‑E matching funds for eligible prevention services?

Consider Whether At that place Is Connected Demand for Additional Funding for Counties. As described above, the state provided effectually $85 million 1‑time funding to counties for kid welfare activities in both 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. Our agreement is counties primarily are using this funding to continue CCR implementation activities, such equally RFA, although we proceed to work with the section to empathize what specific activities counties are using these funds to undertake. Since this funding has been needed for the past two years, the Legislature may wish to ask the administration to explain what has changed that a funding augmentation is not needed in the budget twelvemonth for counties' child welfare responsibilities.

Where Does Child Protective Services Budget Come From / Who Administers Funds,

Source: https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/4558

Posted by: lawsblied1944.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Where Does Child Protective Services Budget Come From / Who Administers Funds"

Post a Comment